Isothermal Navier-Stokes/Korteweg model

Historically, the thermodynamic theory of capillarity was developed by van der Waals under the hypothesis of a continuous variation of density [1]. In that sense, this is the very first diffuse interface theory. Next Korteweg has modified the Navier-Stokes equations to take into account the surface tension force through what we call the Korteweg’s tensor [2]. Those equations are known as the Navier-Stokes/Korteweg model (NSK) which is a popular model for simulating two-phase flows. That model is a low Mach formulation of the Navier-Stokes equations, where \(\rho\) plays the role of phase index. The two-phase behavior is obtained by an appropriate choice of the Equation of State (EoS). The NSK model is an alternative model to the Navier-Stokes/Conservative Allen-Cahn model for two incompressible fluids (see Model of incompressible Navier-Stokes with interface-capturing equation).

Free energy functional with \(\rho\)

For a sake of simplicity of this presentation, we assume an isothermal fluid: the temperature \(T\) will appear in the equation of states but it will be considered as a constant. The free energy is defined by

where \(\rho\equiv \rho(\boldsymbol{x},t)\) is the fluid density which replaces the phase-field \(\phi\) previously used as order parameter for incompressible flows. \(\mathcal{W}(\rho)\) plays the role of double-well, and the gradient energy term is given by the last term \(\kappa |\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho\bigr|^{2}/2\). The coefficient \(\kappa\) is named the capillary coefficient. It will be considered as a constant in this section. As seen in Fundamentals of phase-field theory, the gradient energy term is non-local and it is responsible for the surface tension \(\sigma\) and width \(W\) of diffuse interface.

Double-well potentiel

In two-phase flows literature the free energy density \(\mathcal{W}(\rho)\) can take two different forms. In the first one, it takes a similar form as previously noted \(f_{dw}(\phi)\):

where \(\rho_l\) and \(\rho_g\) are the bulk densities of liquid and gas and the subscript \(_{dw}\) means double-well. That expression is equivalent to the double-well \(f_{dw}(\phi)=Hg_2(\phi)\) of Fundamentals of phase-field theory. In particular, the equilibrium solution of Euler-Lagrange equation is:

The solution of density \(\rho(x)\) follows a hyperbolic tangent profile and varies continuously between a minimum value \(\rho_g\) and maximum value \(\rho_l\). The slope of that variation is controlled by the parameter \(W\) which is the interface width. The expressions of interface width \(W\) and surface tension \(\sigma\) can also be re-used:

Potential and Equation of State

In the rest of this section, we will focus on another way to define the potential \(\mathcal{W}(\rho)\) and we will relate it to the thermodynamic pressure \(p^{eos}(\rho)\) where the superscript \(^{eos}\) means Equation of State.

van der Waals equation of state and Maxwell construction

The equation of state for an ideal gas is given by (1 mole):

which is derived from point-like particles whitout interaction. Expressed with density \(V=1/\rho\) that equation of state takes the expression

where the subscript \(_{pg}\) means perfect gas. That EoS of perfect gas is monotonous: for one pressure corresponds only a unique density. That relationship is also local in the sense that, at a same point \(\boldsymbol{x}\), the pressure \(p^{eos}(\boldsymbol{x})\) is related to the density \(\rho(\boldsymbol{x})\) and temperature \(T(\boldsymbol{x})\). We will see below that the gradient energy term in Eq. (549) is responsible for a non-local pressure \(\mathcal{P}\).

van der Waals equation of state

Van der Waals modified that assumption. A new equation of state was formulated with short range repulsion (excluded volume) and long range attractions:

where \(a\) represents attractive interactions which modify the pressure and \(b\) corresponds to the excluded volume occupied by hard sphere atoms. Those interactions can be described by interactomic potential, e.g. Lennard-Jones. Expressed with density, that Equation of State writes:

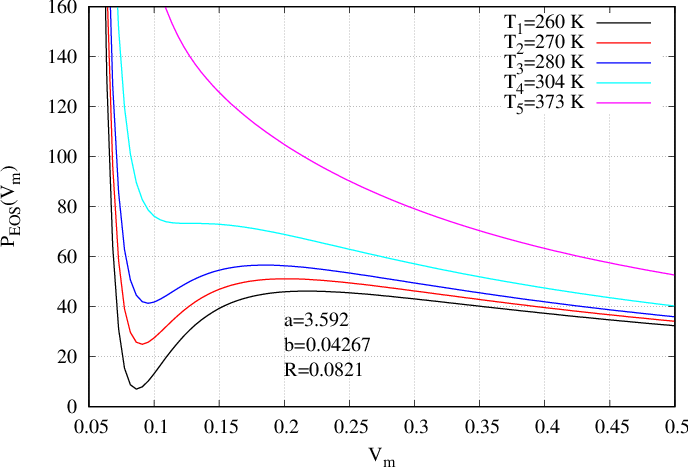

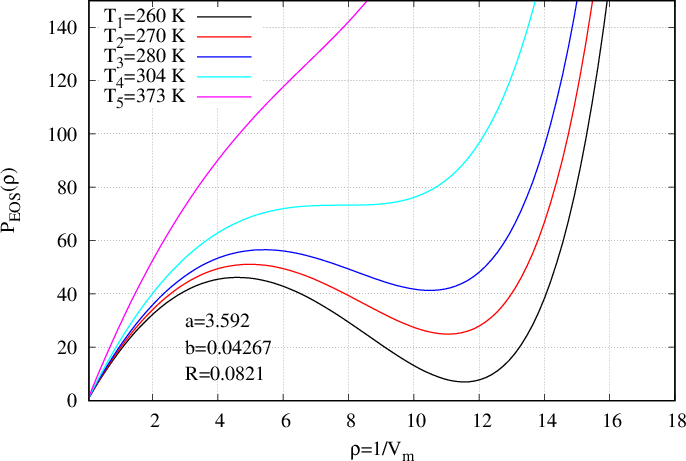

The main advantage of that form of EoS, is that, for certain values of temperature, the EoS is not any more monotonous, and for one pressure corresponds two values of densities. Indeed, on Fig. 51 the pressure is presented as a function of volume \(V\) whereas on Fig. 52 it is presented as a function of density \(\rho\). On those figures, one temperature \(T_5\) (the magenta curve) is above the critical temperature. The curve is monotonous and only one density corresponds to one pressure. For temperature \(T_4\) (cyan curve) there is an inflexion point corresponding to the critical temperature (zero derivative with respect to rho). At last, for three next temperatures \(T_1,T_2,T_3\) (respectively black, red and blue curves), the pressure presents a cubic form enabling the existence of two densities corresponding to one pressure.

Critical point

The critical point corresponds to the presence of an inflexion point on the curve \(p^{eos}(V)\). It is defined by:

The application of those two conditions to the van der Waals EoS, yields a critical point which is defined by:

Free energy density and non-local pressure

From EoS, we can define a thermodynamic potential \(\mathcal{W}(V)\), which is the work (an energy) of pressure force per volume unit:

i.e. with the variable change \(\rho=1/V\):

For van der Waals EoS, such a potential writes:

It is straightforward (derive Eq. (561) wrt \(\rho\)) to show that the thermodynamic pressure \(p^{eos}(\rho)\) can derive from a thermodynamic potential \(\mathcal{W}(\rho)\):

The potential \(\mathcal{W}(\rho)\) is more general because once it is set, we can derive the thermodynamic pressure \(p^{eos}(\rho)\) but also other quantities such as the chemical potential \(\mu_{\rho}^{(0)}\) where the superscript \(^{(0)}\) means “local”. Moreover, we can use it in Eq. (549) and derive other non-local quantities such as the non-local pressure \(\mathcal{P}(\rho,\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho)\) and the non-local chemical potential \(\mu_{\rho}(\rho,\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho)\). Both quantities are called “non-local” because they depend on \(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho\).

The non-local pressure \(\mathcal{P}(\rho,\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho)\) is obtained by applying the definition Eq. (563), but with free energy density \(\mathcal{F}(\rho,\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho)\) replacing the potential \(\mathcal{W}(\rho)\). The partial derivative \(\partial /\partial\rho\) must also be replaced by the variational derivative \(\delta / \delta \rho\) because the two independent variables \(\rho\) and \(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho\) are involded in the free energy density \(\mathcal{F}\):

where the Euler-Lagrange equation is used in the brackets (see Fundamentals of phase-field theory) for the second line and (563) for the third line. Now we see the consequence on pressure of adding a gradient energy term in the free energy density: the pressure is not any more equal to the eos pressure, it is modified by two non-local terms (i.e. depending on \(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho\)), both depending on the capillary coefficient \(\kappa\). The gradient energy term is responsible for the surface tension, the diffuse interface and the modification of pressure which becomes non-local.

In Fundamentals of phase-field theory, we have seen that \(\delta \mathcal{F}/\delta \rho\) is the definition of chemical potential \(\mu_{\rho}\). In the second line of Eq. (564), the term inside the brackets is the non-local chemical potential \(\mu_{\rho}\). Its expression for a van der Waals EoS (i.e. with \(\mathcal{W}\) defined by Eq. (562)) writes

Let us emphasize that the non-local terms in Eqs. (564) and (565) have an impact only at the interface between both fluids or in the vicinity of the interface because in the bulk phases, the densities are constant of values \(\rho_l\) and \(\rho_g\), and consequently their gradients are zero.

Summary of van der Waals EoS

The Van der Waal EoS writes

which can be derived from potential \(\mathcal{W^{vdW}}\):

The chemical potential writes:

Maxwell construction for bulk densities \(\rho_l\) and \(\rho_g\)

Common tangent construction

The van der Waals EoS indicates how the pressure varies as a function of density. Under the critical point, the equilibrium solutions, or bulk densities \(\rho_l\) and \(\rho_g\) are obtained with the Maxwell construction. We remind that the thermodynamic equilibrium is reached when the intensive variables are equal and constant inside the whole domain. More precisely, for two phases of density \(\rho_l\) and \(\rho_g\):

With the definition of thermodynamic pressure Eq. (563), it is straightforward to obtain

This means that \((\rho_l,\mathcal{W}(\rho_l))\) and \((\rho_g,\mathcal{W}(\rho_g))\) lie on a common tangent line of \(\mathcal{W}(\rho)\) of slope \(\mu^{(0)}\).

Graphic interpretation

The graphic interpretation of Maxwell construction is known as an “equal area rule”. That construction states that, for one particular pressure \(P_b\), the bulk volumes (or densities) \(V_{l}\) and \(V_{g}\) are obtained such as

That relation can be interpreted as equal surfaces \(S_{1}=S_{2}\) where the area between \(P_b\) and the upper part of the vdW EoS and the area between \(P_b\) and the lower part of the vdW EoS are equal. For example, with vdW eos:

the bulk pressure \(P_b\) and the two equilibrium densities \(\rho_g\) and \(\rho_l\) are solution of \(S_1=S_2\):

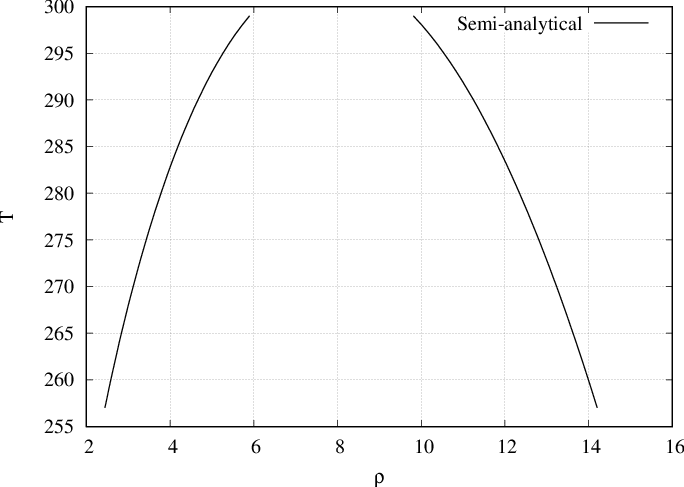

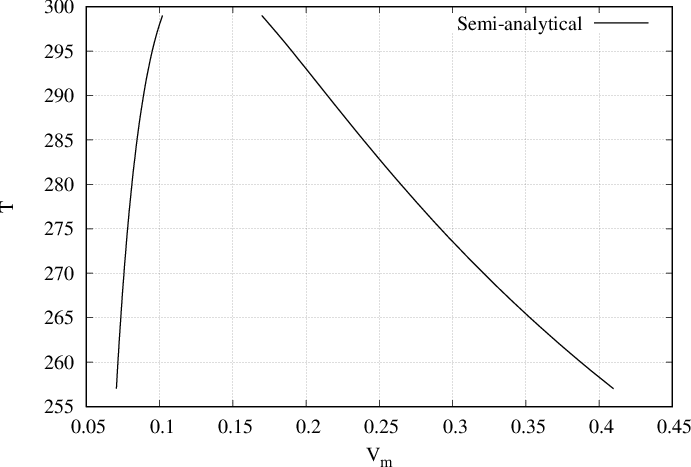

By solving semi-analytically we obtain the equilibrium densities (or coexistence densities) of bulks \(\rho_l\) and \(\rho_g\) for several temperatures as presented in Fig. 53 and Fig. 54. For example, on Fig. 53, at \(T=280\) two fluids will coexist. The first one density \(\rho_g \approx 4\) and the second one of density \(\rho_l \approx 12\).

Pressure tensor and Korteweg tensor

For a sake of simplicity of this presentation, here we follow the argument presented in reference [3] to derive the tensor pressure and the Korteweg’s tensor. As seen in Fundamentals of phase-field theory, when the order parameter is conserved (this is the case for \(\rho\)), the chemical potential \(\mu_{\rho}\) can be interpreted as a the Lagrange multiplier associated with the constraint of mass conservation. The integrand of \(\mathcal{F}\) as well as that of the mass constraint are independent of the spatial coordinates. Consequently, it follows from Noether’s theorem (see [4] sections 12-3 p. 555 and 12-7 p. 588) that there is a corresponding conservation law given by

where the pressure tensor \(\overline{\overline{\boldsymbol{P}}}\) is a tensor of second rank which is given by

where \(\overline{\overline{\boldsymbol{I}}}\) is the identity tensor, and \(\mathcal{L}(\rho,\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho)\) is

where the free energy density is defined by Eq. (549) i.e. \(\mathcal{F}=\mathcal{W}(\rho)+\kappa|\boldsymbol{\nabla}\rho|^2/2\) and the Lagrange multiplier \(\mu_{\rho}\) (or chemical potential) is given by \(\mu_{\rho}=\delta\mathcal{F}/\delta\rho\) (Euler-Lagrange)

It is straightforward to obtain

where we recognize the non-local pressure \(\mathcal{P}\) inside the brackets, but also a second term which gives birth to the surface tension force between both fluids. The second rank tensor

is called the korteweg’s tensor.

Equivalence of tensor pressure

In most of numerical methods that implement the NSK model, the pressure tensor Eq. (575) is not directly discretized because there exist two equivalent algebraic forms which are easier to implement. The first one is the potential form and the second involves the chemical potential.

First form: potential form

The first form is called the potential form and writes:

Demo:

Second form: chemical potential form

with

Demo

As function of potential \(\mathcal{W}\) the chemical potential writes:

and the thermodynamic pressure is:

where in the first line we used the definition of \(\mu_{\rho}\) Eq. (580) with \(\mathcal{W}^{\prime}(\rho)\) derived from Eq. (581).

Mathematical model of van der Waals fluids

The model of Navier-Stokes/Korteweg is obtained from a low Mach formulation of Navier-Stokes equations by simply replacing the gradient of pressure \(-\boldsymbol{\nabla}p\) by the divergence of the pressure tensor \(-\boldsymbol{\nabla}\cdot\overline{\overline{\boldsymbol{P}}}\). That tensor contains the pressure defined by the equation of state and others terms which are responsible for the surface tension force.

Model of Navier-Stokes/Korteweg

The mathematical model is based on the low Mach formulation of the Navier-Stokes equations. The mass balance writes

The impulsion balance equation makes appear the pressure tensor

where \(\overline{\overline{\boldsymbol{P}}}\) is the pressure tensor which is defined by

For numerical implementation, the divergence of pressure tensor \(\boldsymbol{\nabla}\cdot\overline{\overline{\boldsymbol{P}}}\) can advantageously be replaced by one of the two following forms given either by Eq. (577) or by Eq. (578) with Eq. (579).

In Eq. (584) \(p^{eos}(\rho,T)\) is the thermodynamic pressure which is related to the density and temperature by one Equation of State. Several ones exist: the van der Waals EoS (Eq. (566)) can be used or others defined in the next section.

Let us mention that other methods exist to derive the Navier-Stokes/Korteweg models, especially when the coupling with temperature [5] or surfactant [6] are considered. In those references, the constitutive laws (closures for energy flux, expression of stress tensor, etc.) are derived such that the dissipation (given by the Clausius-Duhem inequality) is positive or null. The main advantage of that approach is to derive models of two-phase flows which are thermodynamicaly-consistent. But that rigorous approach has a cost: the algebraic calculations are expensive and are beyond the scope of that introduction.

Other equations of state (EoS)

Several Equations of State (EoS) exist in the literature to simulate two-phase flows: van der Waals, Carnahan-Starling, Peng-Robinson, Redlich-Kwong, etc. The van der Waals EoS is at the heart of this presentation. We present below a summary of other ones.

Carnahan-Starling EoS

The Carnahan-Starling EoS writes:

In Eqs. (566) and (585), the input parameters are \(a\), \(b\) \(R\) and \(T\).

Redlich-Kwong (RK)

Peng-Robinson (PR)

Bibliography

Section author: Alain Cartalade